Currency devaluation has long been a powerful tool and potential hazard in global economics. Whether used deliberately or triggered by crises, it impacts everything from trade balances and foreign debt to household purchasing power. For instance, Argentina’s peso crisis in 2023 slashed wages and triggered mass protests, while Egypt’s recent currency devaluation in 2024 aimed to unlock much-needed IMF support. This article explores the frequency, impact, and statistical profile of currency devaluation episodes around the world. Dive in to understand how these shifts unfold, what drives them, and why they matter more than ever.

Editor’s Choice

- Venezuelan bolívar dropped 51% against the USD in the first half of 2025 amid hyperinflation.

- South Sudanese pound fell 15% YTD, second-worst globally due to oil disruptions.

- By mid-2025, the Argentine peso has weakened by over 10%, reflecting ongoing inflation and the crawl-like FX regime implemented post-2023.

- Turkish lira declined about 20% YTD in 2025, hitting a record low of around 42.4 per USD by December.

- Six of the top 10 biggest drops in 2025 were African currencies, including the Libyan dinar, 9%.

- US dollar index fell about 10.8% in the first half of 2025, its sharpest six‑month drop since the early 1970s.

Recent Developments

- In 2024, Nigeria’s naira devalued by 43% against the U.S. dollar following government reforms and the liberalization of its foreign exchange system.

- Egypt devalued its currency by over 50% in a single day in March 2024 to meet IMF loan conditions.

- Pakistan’s rupee faced continued downward pressure, losing 30% of its value in 2024 alone, driven by dwindling reserves and political instability.

- Argentina implemented a crawling peg system in late 2023, yet the peso still depreciated 55% year-on-year amid hyperinflation.

- Lebanon’s pound fell to record lows in 2024, experiencing over 90% depreciation from pre-crisis levels.

- Ghana’s cedi weakened by 22% in 2024 despite IMF assistance, with inflation still running above 35%.

- The Venezuelan bolívar continues to experience chronic depreciation, losing over 99% of its value since 2013.

Most Influential Currencies

- U.S. dollar dominates with a 49.68% global share, nearly half of all SWIFT-based transactions.

- Euro follows at 22.24%, confirming its role as a strong secondary reserve currency.

- Pound sterling ranks third with 6.51%, still influential despite post-Brexit uncertainty.

- Japanese yen and Chinese renminbi hold 4.03% and 3.50%, showing continued relevance in Asia.

- Canadian dollar edges out others in the 3% range at 3.18%.

- Emerging currencies like the Hong Kong dollar (1.73%), Australian dollar (1.43%), and Singapore dollar (1.31%) maintain a notable global presence.

- Several European currencies, the Swiss franc (0.96%), the Swedish krona (0.88%), Polish zloty (0.74%), remain influential despite small market sizes.

- Nordic currencies such as the Norwegian krone (0.39%), the Danish krone (0.39%), and the New Zealand dollar (0.33%) continue to appear in top-20 flows.

- South African rand, Mexican peso, and Thai baht each hold 0.26%, reflecting modest global use.

- Hungarian forint and Malaysian ringgit round out the list with 0.21% each, signaling minor but measurable cross-border relevance.

Global Perspective on Currency Devaluation Trends

- Since 2010, over 60 emerging and frontier markets have experienced currency devaluations exceeding 20% in a single year.

- Asia and Africa have seen the highest concentration of recent devaluation events between 2020 and 2025.

- Global inflation and interest rate hikes since 2022 have triggered broad currency weakness in non-dollar economies.

- As of Q1 2025, 47% of low-income developing countries are facing a moderate-to-high risk of debt distress, increasing devaluation potential.

- Countries with pegged or managed exchange-rate regimes are more likely to experience abrupt devaluation when pressure mounts.

- Central banks in 28 countries intervened in FX markets in 2024 to defend their currencies.

Definition & Measurement of Devaluation

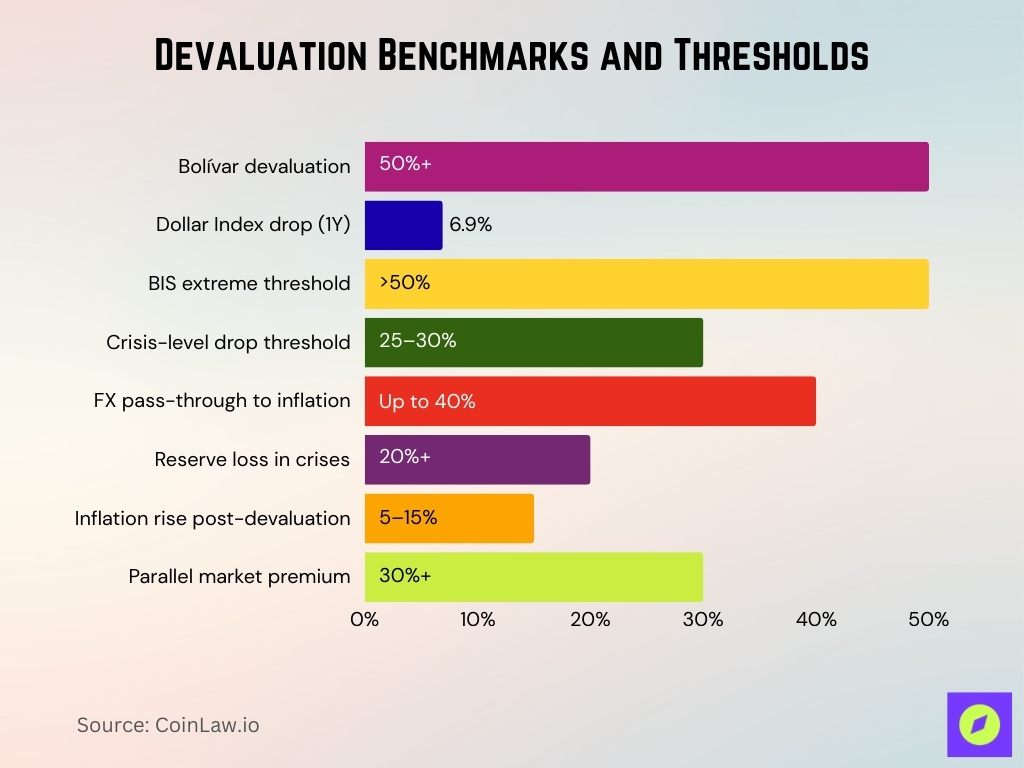

- The Venezuelan bolívar devalued over 50% against the U.S. dollar by mid-2025, classified as extreme by BIS standards.

- The dollar index showed a 6.9% decline over 12 months ending late 2025.

- BIS defines “extreme devaluation” as annual currency depreciation above 50%, often signaling crisis conditions.

- A crisis-level devaluation threshold is a 25–30% currency drop over 12 months.

- Exchange rate pass-through to inflation varies but can reach as high as 40% in volatile emerging markets.

- Reserve depletion during devaluation events can exceed 20% of total reserves in severe cases.

- Inflation surges following devaluation, averaging 5–15% spikes within a year.

- Parallel market spreads during devaluation crises can widen to over 30% above official exchange rates.

Historical Patterns of Major Currency Crashes and Devaluations

- Venezuelan bolívar crashed 51% against the USD in the first half of 2025, the worst major currency drop amid hyperinflation.

- South Sudanese pound depreciated 15% YTD 2025, second-worst amid oil export losses of $7 million daily.

- Argentine peso dropped 13% against USD through mid-2025, echoing repeated historical crises.

- Six of the top 10 currency crashes in 2025 occurred in African nations, mirroring the 1980s debt crisis frequency.

- Emerging market currencies broadly appreciated post-dollar peak in Jan 2025, reversing 5% depreciation trend.

- Angola dollar bonds triggered $200 million margin call in Apr 2025, shutting access like historical liquidity crises.

1930s Gold Standard Collapse

- British pound’s effective exchange rate fell 23% between Q2 and Q4 1931 after the gold standard abandonment.

- UK interest rates dropped from 6% to 2% post-1931 devaluation, spurring export growth.

- US real output plunged 30% and industrial production 47% during the gold standard collapse phase.

- Money supply contracted nearly 30% from fall 1930 to winter 1933 under rigid gold rules.

- Britain lost over £50 million in gold reserves in the weeks before the September 1931 suspension.

- 60% of League of Nations currencies were restored to gold by 1925, and collapsed by 1932.

- Countries exiting gold early saw industrial production grow 7% faster annually, 1932-1935.

- US unemployment hit 25% by 1933 amid gold standard deflation pressures.

- 9,000 of 25,000 US banks failed by 1933 during the gold-backed monetary contraction.

Currency Gainers and Losers vs. US Dollar (YTD)

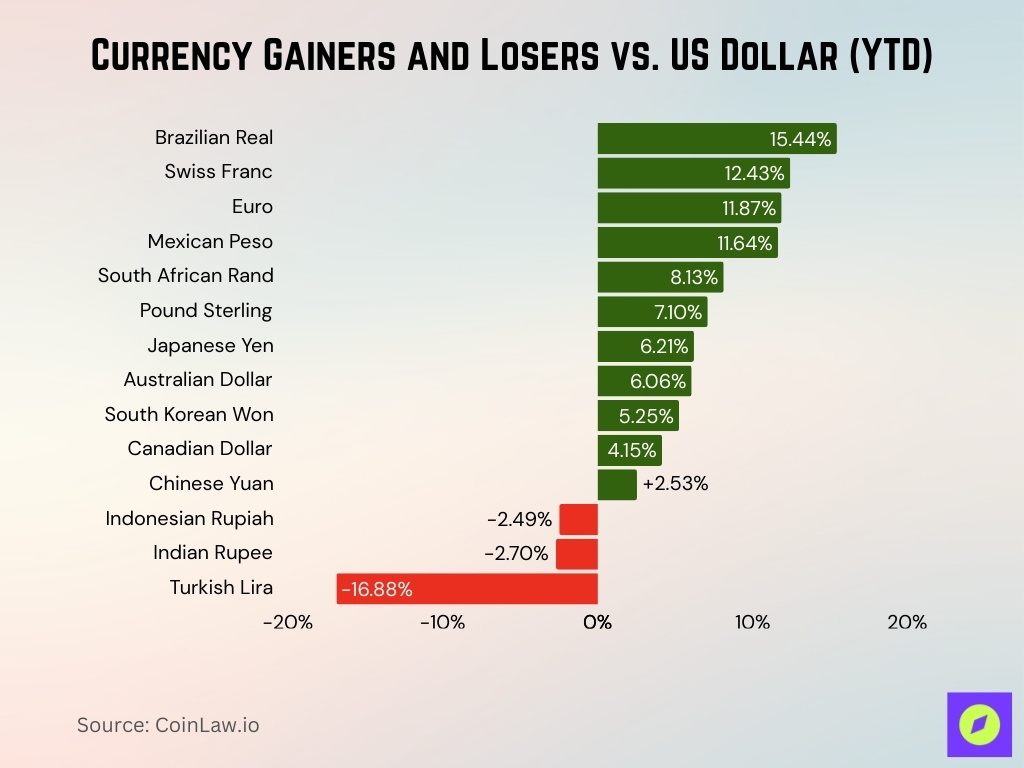

- Brazilian real tops the chart with a +15.44% gain against the US dollar.

- Swiss franc surged +12.43%, reflecting investor demand for safe-haven currencies.

- Euro climbed +11.87%, boosted by stronger-than-expected EU growth.

- Mexican peso posted a strong +11.64% rise, supported by trade and remittances.

- South African rand gained +8.13%, helped by commodity exports.

- British pound appreciated by +7.10%, reflecting resilience in UK markets.

- Japanese yen increased by +6.21%, partially reversing earlier depreciation.

- Australian dollar rose +6.06%, fueled by demand for raw materials.

- South Korean won added +5.25%, showing regional economic strength.

- Canadian dollar strengthened by +4.15%, supported by oil exports.

- Chinese yuan edged up +2.53%, reflecting controlled FX policies.

- Indian rupee dropped -2.70%, pressured by rising imports and capital outflows.

- Indonesian rupiah slid -2.49%, hit by inflationary concerns.

- Turkish lira plunged a dramatic -16.88%, the worst-performing major currency of the year so far.

Latin American Debt Crisis

- Latin America’s external debt surged from $29 billion in 1970 to $159 billion by 1978.

- By 1982, regional debt reached $327 billion, up from $159 billion in 1978.

- 16 Latin American countries rescheduled debts after Mexico’s $80 billion default in 1982.

- Real wages in urban areas fell 20-40% during the 1980s debt crisis decade.

- Regional real GDP growth averaged just 2.3% from 1980-1985, per capita negative 9%.

- Latin America paid back $108 billion to creditors between 1982-1985 amid recession.

- The fiscal deficit to GDP ratio more than doubled in major debtors from 1978 to 1982.

- Debt rose from 30% of GDP in 1979 to nearly 50% by 1982 for large economies.

- Brazil’s real wages dropped 33% between 1981-1985 during the crisis peak.

Asian Financial Crisis

- Thai baht depreciated by 60% against the U.S. dollar by October 1997.

- Indonesian rupiah fell to 1/5th of its June 1997 value against the dollar.

- South Korean won depreciated by nearly 46% in real terms from June to December 1997.

- Indonesia suffered a 12% GDP decline in 1998 following the rupiah collapse.

- Thailand’s stock market dropped 75% amid the baht devaluation.

- ASEAN economies saw foreign debt-to-GDP ratios surge from 100% to 167% in 1993-1996.

- IMF bailout for Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea totaled $40 billion.

- Indonesia’s rupiah plunged from 2,600 to over 14,000 per U.S. dollar in 1998.

- South Korea’s GDP fell 6.2% in 1998, with construction contracting 23.5%.

GDP Losses from Collapses

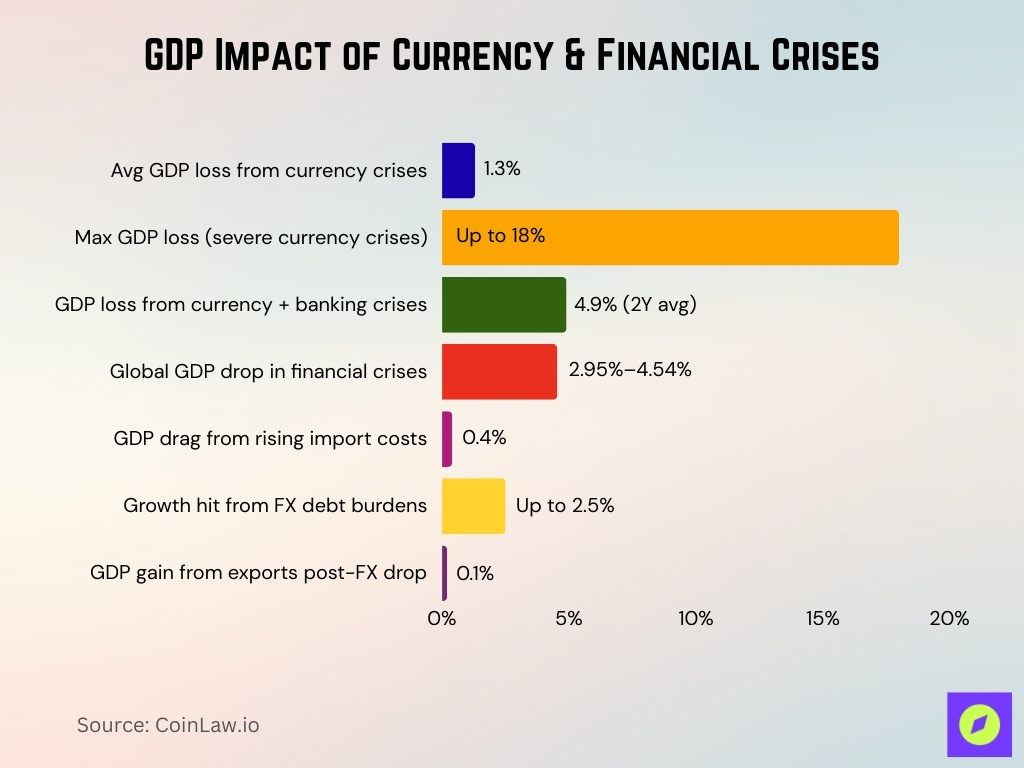

- Currency crises lead to average GDP losses of 1.3% and up to 18% in severe cases.

- Combined currency and banking crises reduce GDP by about 4.9% on average over two years.

- Global financial crises decreased worldwide GDP by between 2.95% and 4.54%.

- Rising import costs post-devaluation suppress business investment by approximately 0.4%.

- Foreign currency debt burdens rise post-devaluation, slowing growth by up to 2.5%.

- Export volume gains after depreciation raise GDP by roughly 0.1% but are offset by inflation and import cost rises.

Worst Hyperinflation Cases

- Argentina hit 3,000% annual inflation in 1989 amid debt crisis fallout.

- Brazil recorded 81.3% monthly inflation in March 1990 hyperinflation peak.

- Bolivia reached 60,000% annualized inflation between May and August 1985.

- Peru suffered 7,000% inflation in 1991, with per capita GDP dropping to $1,908.

- Latin America’s real wages fell 20-40% in urban areas post-1980 debt crisis.

- Regional inflation averaged nearly 500% at the end of the 1980s across key countries.

- Brazil saw 71.9% monthly inflation in January 1990 hyperinflation started.

- Argentina’s inflation exceeded 2,600% annually in both 1989 and 1990.

Currency Peg Failures

- In 1994, the Mexican peso was suddenly devalued by about 15% as the peg came under speculative attack.

- After the initial move, the peso ultimately lost around 50% of its value against the U.S. dollar within months.

- When the U.K. exited the ERM in 1992, sterling fell by about 15% against the Deutsche Mark in a short period.

- Britain abandoned the gold standard in 1931 after losing about £50 million of gold and foreign exchange loans in a few weeks.

- Countries that left gold early in the 1930s saw GDP recover several percentage points faster than late-exiters like France and Belgium.

- On average, currencies decline by over 50% during documented collapse episodes in empirical studies.

- Such currency collapses leave real GDP 2–6% lower than trend three years after the event.

- Empirical work shows currency and banking crises reinforce each other, with twin-crisis probability rising markedly after a peg break.

- Under pegged regimes, average inflation runs near 8%, compared with 16% under floating regimes in cross-country IMF data.

Statistics on Frequency and Severity of Devaluation Events

- There were 414 currency crises globally between 1950 and 2019, averaging 6-7 events per year.

- From 1975 to 2007, there were 201 currency crises documented under standard definitions.

- During the 2008–2009 financial crisis, 23 countries experienced currency depreciations of 25% or more.

- About 50% of currency crises coincide with sudden stops in capital inflows, lasting on average 4 quarters.

- High foreign currency debt significantly increases the severity of devaluation impacts on debt-to-GDP ratios.

- Average currency devaluation in crises often exceeds a 50% decline against major currencies.

- Devaluation pass-through to inflation ranges between 11% to 26% over four quarters, with recent moderation.

- Modern large depreciations are often comparable to historical episodes in size and frequency.

- Currency crises typically cause real GDP to be 2–6% below trend three years post-event.

Exchange-rate Regime and Policy Responses

- Fixed or pegged exchange rate regimes were present in 45% of countries experiencing currency crises in 2025.

- Economies with flexible exchange rates absorb external shocks 30% more effectively on average than rigid peg regimes.

- Over 60% of countries shifted toward floating or managed-float regimes after a sharp depreciation since 2000.

- Devaluation increases foreign-denominated debt burdens by an average of 15-25% in domestic currency terms.

- Governments raised interest rates by an average of 200 basis points during currency defense attempts in 2024-2025.

- Fiscal consolidation, combined with allowing currency float, helped reduce inflation by 4-6 percentage points within a year.

- Strong institutions lower the probability of repeated devaluation episodes by up to 35%.

- Pegged regimes stabilized short-term exchange rates but raised vulnerability to abrupt failures in 70% of cases reviewed.

Inflation Rates During Crises

- A study of 41 major devaluations found inflation rises in most cases, often significantly.

- Roughly 70% of devaluation episodes see higher inflation post-crisis.

- Inflation increases by one-third of the devaluation rate in the devaluation year.

- 30% of cases show no inflation rise due to austerity or weak demand conditions.

- Import-dependent countries experience sharper CPI rises after devaluation shocks.

- The pass-through coefficient averages 0.5-0.6 from depreciation to inflation over 12 months.

- 10% depreciation typically raises inflation by 11.8% in subsequent periods.

- Firms with imported inputs face 15-25% cost increases, contributing to price pressures.

Debt Distress Episodes

- Sharp devaluation raises debt-to-GDP ratios by 10-20% in countries with high foreign currency debt.

- Foreign currency debt share reached 25% of total debt by 1985 in many emerging markets.

- Sovereign debt restructurings numbered over 600 cases across 95 countries since 1950.

- High foreign currency debt leads to deeper recessions after devaluation episodes.

- Twin currency-banking crises occur together in emerging markets with a strong correlation.

- Capital inflow bonanzas nearly double banking crisis probability in the following two years.

- Average sovereign default spell lasts 7-10 years, often requiring multiple restructurings.

- Peso depreciation was estimated to add roughly PHP 58–60 billion to the Philippine national debt via valuation effects in late 2025.

Socioeconomic Effects, Purchasing Power, Poverty, Social Stability

- Inflation after devaluation reduces household purchasing power by up to 20-30% within a year.

- Real returns on savings accounts are negative by about 1.8% annually due to inflation outpacing interest rates.

- Poverty rates rise by approximately 7% after significant currency devaluation events.

- Social instability increases with inflation-driven declines in living standards, affecting over 25% of vulnerable populations.

- Corporate insolvencies rose 5% in 2025, linked partly to foreign currency debt burdens.

- Consumer confidence index fell to 88.7 in November 2025, the lowest since April 2021.

- Dollarization spikes after crises, with up to 70% of households in some markets holding foreign currency deposits.

- Repeated crises exacerbate income inequality, increasing the Gini coefficient by approximately 3-5 points.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

In about 70% of significant devaluation episodes, inflation rises noticeably in the 1–2 years following the currency drop.

Severe crises combining currency collapse and financial instability can result in GDP losses up to 18%.

Analysts in October 2025 flagged three “neutral / watch” emerging-market currencies as being under structural pressure.

Conclusion

Currency devaluation remains a powerful economic force with broad consequences. While it can support export competitiveness, it frequently leads to inflation, weakened growth, debt distress, and social strain. Historical and recent data underscore that devaluations often emerge in economies with fragile exchange rate regimes, heavy foreign currency debt, or limited fiscal resilience. As global volatility continues, understanding these patterns helps policymakers and analysts navigate risks and anticipate impacts on trade, living standards, and financial stability.