From collapsed petro-states to financial powerhouses facing ruin, loan defaults, especially at the sovereign level, can devastate markets, displace governments, and rattle global confidence. This article examines the most financially catastrophic defaults in modern history. Whether through political mismanagement or global economic shocks, these defaults didn’t just rewrite balance sheets; they reshaped entire economies.

Key Takeaways

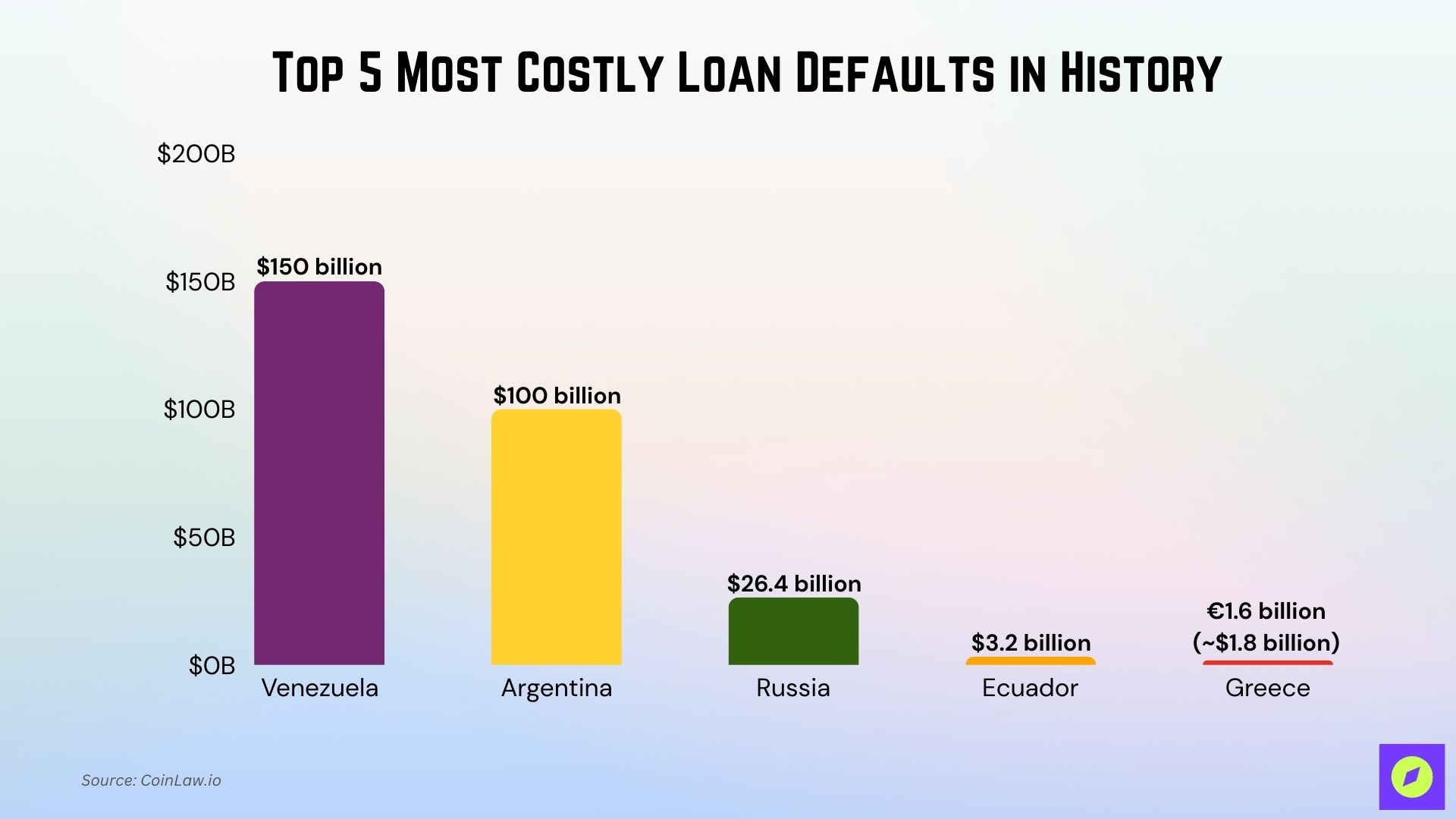

- Venezuela holds the record for the largest sovereign default, with $150 billion in unpaid debt amid an ongoing humanitarian and economic crisis.

- Argentina’s 2001 default remains one of the most infamous, involving $100 billion in government debt.

- Russia is facing rising consumer-level defaults, with household non-performing loans (NPLs) reaching approximately $26.4 billion in 2025.

- Ecuador’s $3.2 billion default in 2008 was a bold, politically motivated move to reject “illegitimate debt.”

- Greece’s 2015 IMF default, while smaller at €1.6 billion (~$1.7 billion), marked the first IMF default by a developed nation.

Top 5 Most Costly Loan Defaults in History

This reveals how massive financial missteps can shake economies and reshape global markets. These cases highlight the risks of debt, poor management, and the far-reaching consequences of default.

| Country | Year of Default | Amount Defaulted | Why It’s Costly | What Happened |

| Venezuela | 2017–Ongoing | $150B | Largest sovereign debt collapse in Latin America; paralyzed government finances | Hyperinflation, oil price crash, and sanctions led to widespread non-payment of bonds |

| Argentina | 2001 | $100B | At the time, the biggest sovereign default in global history | Debt suspension, bank freezes, and currency collapse triggered years of social and economic turmoil |

| Russia | 2025 | $26.4B | Consumer defaults exposed deep financial stress in the economy | Mortgage and auto loan defaults nearly doubled, straining banks and reducing credit availability |

| Ecuador | 2008 | $3.2B | Small in size but politically bold, it undermined investor confidence | The government declared bonds illegitimate, defaulted, then repurchased debt at steep discounts |

| Greece | 2015 | €1.6B (~$1.8B) | First developed nation to default on the IMF, sparking eurozone instability | Missed IMF repayment, imposed capital controls, and entered new bailout negotiations |

1. Venezuela

Venezuela’s default is one of the most extreme debt collapses in modern history, driven by a toxic mix of hyperinflation, plummeting oil revenues, and political turmoil. The government stopped servicing its debt obligations as the economy spiraled into crisis, triggering widespread humanitarian and financial consequences.

- Amount Defaulted: $150 billion

- Year of Default: 2017–Ongoing

- Why It’s Costly: It stands as the largest sovereign default in Latin America, locking the country out of global capital markets and devastating public infrastructure.

- What Happened: The country ceased bond payments amid sanctions and economic freefall, leading to a prolonged state of default with no formal restructuring.

2. Argentina

Argentina’s 2001 debt default marked one of the most dramatic economic implosions of the early 21st century, plunging millions into poverty and triggering political unrest. The scale of the default and the subsequent decade-long standoff with creditors left a lasting scar on the country’s financial reputation.

- Amount Defaulted: $100 billion

- Year of Default: 2001

- Why It’s Costly: It was, at the time, the largest sovereign default in history and forced years of litigation, social instability, and restructuring challenges.

- What Happened: Amid currency collapse and a deep recession, Argentina suspended debt payments, froze bank accounts, and enacted harsh austerity measures as default rippled across its economy.

3. Russia

Russia’s default issue in this context stems from a surge in household-level non-performing loans, revealing systemic financial strain amid broader economic headwinds. While not a classic sovereign default, the impact has rippled through its consumer lending and banking sectors.

- Amount Defaulted: $26.4 billion

- Year of Default: 2025

- Why It’s Costly: The growing burden of unpaid mortgages and auto loans is straining financial institutions and reflects deeper cracks in the domestic economy.

- What Happened: As interest rates rose and economic pressures intensified, defaults on consumer debt spiked, nearly doubling the value of overdue loans and undermining lending stability.

4. Ecuador

Ecuador’s default was a rare instance of a country refusing to repay its debt, not due to insolvency, but on ethical and legal grounds. The government labeled a portion of its bonds illegitimate and executed a deliberate default to reduce its debt load.

- Amount Defaulted: $3.2 billion

- Year of Default: 2008

- Why It’s Costly: Though modest in size, it was politically bold and financially disruptive, creating ripple effects across investor confidence in emerging markets.

- What Happened: Ecuador halted payments on specific bond issuances and later repurchased them at a significant discount, dramatically slashing its outstanding liabilities.

5. Greece

Greece’s IMF default shocked the world as it became the first developed country to fall into arrears with the global lender, threatening the integrity of the eurozone. The event underscored the vulnerabilities of even advanced economies during periods of fiscal crisis.

- Amount Defaulted: €1.6 billion (~$1.8 billion)

- Year of Default: 2015

- Why It’s Costly: The default triggered capital controls, banking instability, and intense negotiations to prevent Greece’s exit from the euro.

- What Happened: After years of austerity and recession, Greece missed a critical IMF repayment, prompting fears of contagion across Europe and forcing the country into a third bailout program.

Common Causes of Major Loan Defaults: Why Economies and Companies Collapse

Loan defaults do not happen overnight; they usually build over years of financial mismanagement, poor oversight, or external shocks. By examining past crises, several recurring patterns consistently emerge as the root causes:

- Excessive leverage: Borrowers, whether governments, corporations, or individuals, take on more debt than they can sustain, leaving no buffer for downturns.

- Fraud and misreporting: Corporate scandals such as WorldCom or Enron show how accounting manipulation can inflate valuations until a sudden collapse.

- Macroeconomic shocks: Sudden oil price crashes, global recessions, or currency devaluations often push debtors into insolvency.

- Political instability: Leadership changes, weak institutions, or policy reversals undermine investor trust and repayment capacity.

- Speculative bubbles: Real estate booms, dot-com surges, or crypto manias fuel risky borrowing, with defaults following once bubbles burst.

- Global contagion: As seen in the 2008 financial crisis, interconnected markets can turn one default into a worldwide chain reaction.

Recovery and Restructuring Outcomes: How Defaults Are Managed After the Fall

While defaults can be devastating, they also open the door to restructuring and eventual recovery. Each case reveals different paths that debtors and creditors take to stabilize balance sheets and rebuild confidence:

- Debt-for-equity swaps: Creditors accept ownership stakes in exchange for reduced debt, allowing companies to continue operating.

- Government bailouts: States step in to rescue “too big to fail” firms, as in General Motors’ 2009 restructuring.

- International assistance: Sovereigns often turn to the IMF or World Bank for refinancing packages, albeit with strict austerity conditions.

- Legal restructuring: Bankruptcy courts oversee corporate reorganizations, ensuring fair treatment of creditors while preserving viable assets.

- Bond buybacks at discounts: Strategies like Ecuador’s 2008 default allow countries to retire debt at a fraction of face value.

- Gradual re-entry to markets: After years of reforms and settlements, nations like Argentina eventually regain investor access and rebuild credit ratings.

Conclusion

The costliest loan defaults in history serve as stark reminders of the fragility of global finance. From Venezuela’s sovereign collapse to Lehman Brothers’ systemic failure, each case reveals how debt excesses, poor governance, and external shocks can spiral into crises. The key lesson is simple yet urgent: while defaults may be inevitable, their devastating scale is often preventable through prudent risk management, transparency, and strong institutional safeguards.